Michael Julian, board member since 2016, has enthusiastically supported Wily since our first year of working with students. He has spoken about his personal experiences as a college student without family support at several Wily events and shares his story with us here.

1. Please tell us a little bit about your life.

I live in Concord, Massachusetts, with my wife and eight-month-old daughter. I have spent much of my free time over the last five years renovating our historic house with the help of friends. Since graduating from Bowdoin College, I have worked all over the world in the technology field, living in Singapore and Hong Kong.

2. Why Wily? What drew you to our mission?

I was emancipated at the age of 17. I understand what it is like to attend college without support and not to have a home to visit over the holidays and when school is closed.

I can relate to the experience of our Scholars, growing up with five siblings in rural poverty, being exposed to drugs and alcohol in a volatile household, and experiencing the frequent involvement of social services.

Following my emancipation, I worked several jobs throughout high school and went from friend’s couch to friend’s couch, until my senior year when my baseball coach of many years and his wife took me in. I wanted to succeed and take care of my family — which is a Sisyphean task when you grow up with poverty-fueled thinking. Like the Wily Scholars, I often felt — and still feel — like I could never do enough.

I have personally seen many talented and capable people with similar challenges fall through the cracks. I see the obstacles that Wily Scholars are facing, and I want to help.

3. You had a complicated early family life. How did that impact your arrival and first year at Bowdoin?

I applied to college with no SAT prep. I chose my schools randomly, without guidance or any models of how to navigate the process. I was simply oblivious.

Despite my haphazard college process, I was accepted to Bowdoin College in Maine and dropped off by my friend’s mom. In order to make it all work, I accepted multiple jobs on and off campus. My focus on being a student was diluted by the need to pay my bills. It was hard to focus on thriving in college when I was used to functioning in survival mode.

My independence and history created other significant obstacles my freshman year. At times it complicated relationships with my peers. My freshman year, I moved my bed into the living area in my dorm room. I am social by nature and was chronically oversharing. I felt as though I needed to constantly explain myself. I was looking for safety in an unfamiliar environment. I was not prepared for simple questions, such as “What do your parents do?”

In many ways I was leading a double life. I had a “fake it until you make it” attitude. In general, it’s hard to juxtapose life on a college campus with a family situation like mine. You have to manage the guilt. For example, I enjoyed Bowdoin’s famous dining hall with its abundance of food, while my family members struggled with homelessness and addiction. One tends to want to share what one has earned — I so wanted my siblings to have the college experience.

More concretely, I had to manage school breaks and holidays, each time figuring out where I would go and who I would stay with. At times, I remained on campus during the winters and summers while my peers headed home. Additionally, I had a particular issue managing the exposure to alcohol, trying to wrap my mind around fun and safe partying when substance abuse robbed me of my childhood.

“Do I belong here?” was a question I often grappled with, as would any 18-year-old, but it was exponentially more potent for me with the overlay of a traumatic family background.

4. Looking back, is it clear to you that without intervention your experience would not have been the same?

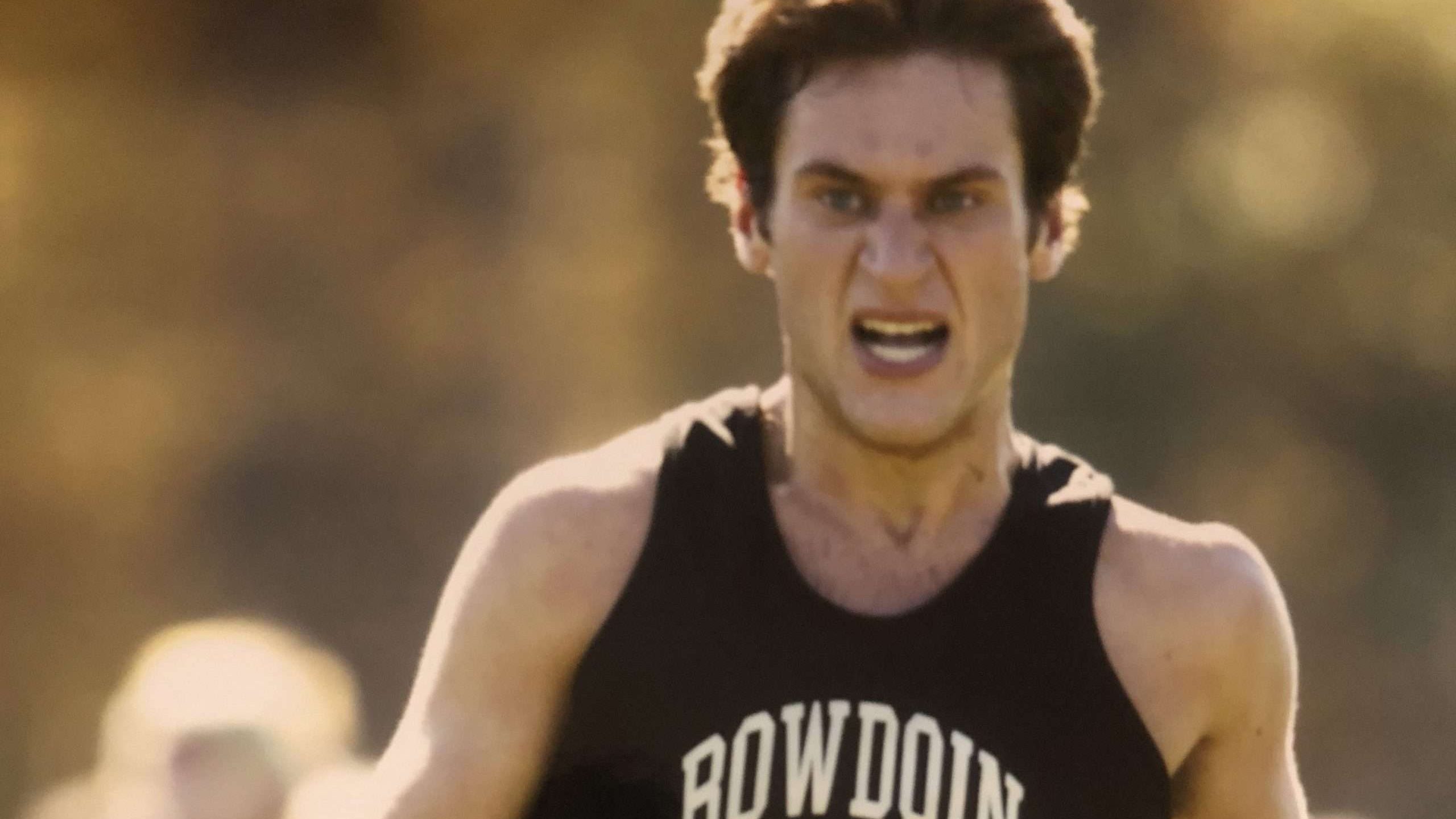

I would have made it through Bowdoin without the wonderful support of Allen Delong, but it would not have been the same. Allen gave me an on-campus job where I could also study. Once we connected, I no longer had to remove myself from the experience of Bowdoin in order to make ends meet. Another inuence was my cross country and track coach, Peter Slovenski, who welcomed me to the team (even though I wasn’t very good) and even employed me at his summer camp.

From there, I was able to take advantage of on-campus resources. I began to heal by attending counseling, building a cohort of close friends and mentors, and participating in internships. Looking back, I feel like I learned how to be normal. I surrounded myself with people to look up to — peer models I could observe — and I learned what it is like to be okay.

5. What else would have helped you while you were in college?

I wish I had a “Wily Network” back then. I had to learn a lot of lessons by trial and error. I wish there had been a program for students in my situation who were attending the school.

6. Is there anything more you’d like the public to know about why they should invest in Wily Scholars?

Even at the best schools, like Bowdoin, some people fall through the cracks. I’m lucky. I wish more people like me had the chance to succeed; I’ve seen many people end up going down the wrong path.

Look around at your peers and colleagues. Statistically, only 10% of students with backgrounds like mine make it to college, and only 3% ever graduate. It’s much easier to give up than to make it through.

If students aren’t able to build coping mechanism skills for trauma at this pivotal juncture, the likelihood of being a productive member of society post-college is severely diminished. My story is an anomaly, and that is why I am so passionate about working with the Wily Network — because I want to make it the norm.